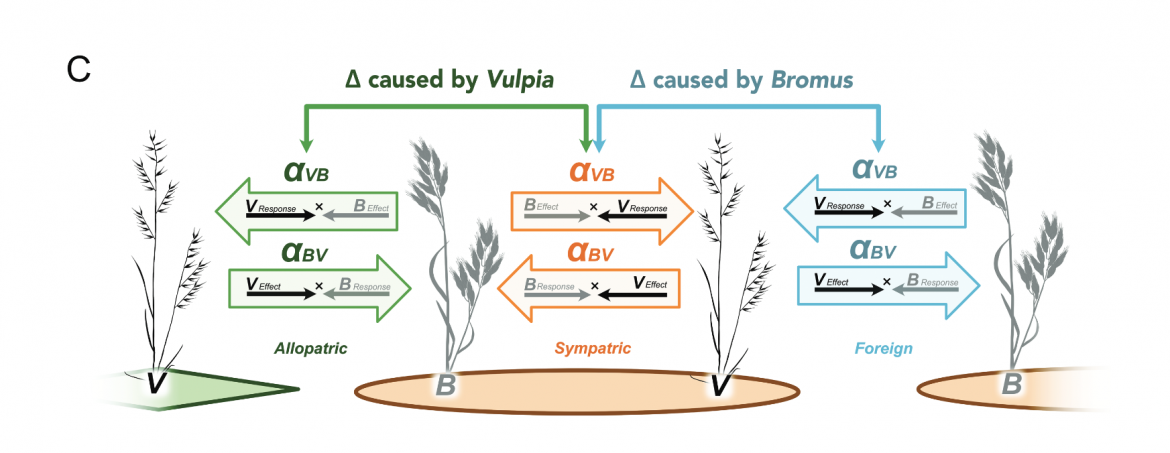

Figure 1C shows what the response and effect are and how their evolution can be attributed to each species. Each single pairwise interaction coefficient, for example, aVB (per capita impact of Bromus on Vulpia) is a product of two parts: Bromus’s effect and Vulpia’s response. To maintain consistent language, we only ever use terms“response” and “effect” to describe these two components that makeup any one competition coefficient, whereas to refer to an entire competition coefficient (e.g.,aVB), we use terms “impact on ”or“ sensitivity to ”the competing species, depending on whether the coefficient is being described from Bromus’s or Vulpia’s perspective, respectively. Arrows show how comparing competition coefficients between evolutionary history treatments can isolate each species’ contribution to the evolution of each inter-action coefficient (see fig. 4). As an example, by comparing a VB between allopatric and sympatric evolutionary histories, any observed difference is due to evolved differences in Vulpia’s response, as Bromus’s effect is held constant.

Abstract

Competition drives evolutionary change across taxa, but our understanding of how competitive differences among species directs the evolution of interspecific interactions remains incomplete. Verbal models assume that interspecific competition will select for reducing a species’ sensitivity to competition with their opponent; however, they do not consider the potential for other demographic components of competitive ability to evolve, specifically, interspecific effects, intraspecific interactions, and intrinsic growth rates. To better understand how competitive ability evolves, we set out to explore how each component has evolved and whether their evolution has been constrained by trade-offs. By setting sympatric and allopatric populations of an annual grass in competition with a dominant invader, we demonstrate (1) that in response to interspecific competition, populations can evolve increased competitive ability through either reduced interspecific or, surprisingly, reduced intraspecific competition; (2) that trade-offs do not always constrain the evolution of competitive ability but rather that parameters may correlate in ways that mutually beget higher competitive ability; and (3) that the evolution of one species can influence the competitive ability of its opponent, a consequence of how competitive ability is defined ecologically. Overall, our results reveal the complexity with which demographic components evolve in response to interspecific competition and the impact past evolution can have on present-day interactions.